Tactics 101 068 – Task Organization

“Generally, management of the many is the same as management of the few. It is a matter of organization.”

Sun Tzu

LAST MONTH

In our last article, we focused on the decision-making tool – The Decision-Support Template (DST). As we stressed, The DST is a tool that is a tremendous aid for a Commander in making timely, and hopefully anticipated decisions. In striving to assist you in understanding this tool, we keyed on several areas. These included providing some historical examples of decision-making on the battlefield, defining The DST and its’ components, and concluding with a practical example of The DST. In the final analysis, decision-making is normally the difference between winning and losing. The smart Commander will equip himself with the tools he needs to give him an advantage. The DST is clearly one of those tools.

THIS MONTH

One of the most important actions during the planning process is determining your task organization. It’s really pretty simple. You can create the most brilliant plan ever devised by man. Yet, if you have not organized your forces effectively to fight that plan; you are setting the conditions for failure. In this article, we discuss how you effectively task organize those forces. We will focus on the answering the following questions:

1) What is the definition of task organization?

2) What are the principles when task organizing?

3) What do you need to know before you task organize your forces?

4) When do we task organize our forces?

5) How will a well-thought out task organization assist you in achieving mission accomplishment?

6) What are the command relationships that exist in a task organization?

7) What are the support relationships that exist in a task organization

8) What are some of the techniques in articulating a task organization?

There is much to cover, but we believe we have organized our article for success. Let’s begin.

What is the definition of task organization?

It is the process of temporarily allocating your forces (and determining the command and support relationships) in order to set the conditions for achieving this particular mission. Let’s dissect a couple parts of this definition. First, a task organization is not locked in stone – it is temporary and specific to the mission. Just as every new mission should result in a new mission analysis, so should every new mission result in an analysis of the task organization. A task organization which has developed for one mission may not be the right one for the next mission. The determination of the command and support relationships is critical. This can have an effect on everything from reporting procedures to who a unit ultimately takes orders from to logistical support.

What are the principles when task organizing?

There are two key principles that should guide your development of a task organization. These are:

1) You want to ensure you are doing everything you can to maintain cohesive teams within your unit. This is critical because this obviously can have a huge positive effect on operations on the ground. The more cohesive your subordinate teams are; the better their ability to work as one. So what can you do to assist you in this? Above all, try to make as little changes as possible and keep habitual associations as much as you can. For instance, if an armor platoon is used to working with a mechanized infantry company; it is a habitual relationship and clearly there is cohesion. If this is not feasible (and many times it won’t be) you try to make these changes as soon as possible. This provides additional time that can be used for training or at least for units to acquaint themselves with one another. Remember, do not make changes on your task organization unless the advantages trump the disadvantages.

2) When creating a task organization, you must ensure you do not exceed the ability of a unit to control the subordinate units you have placed under it. Simply put, a commander can only effectively control a certain number of subordinate units. The rule of thumb is this is anywhere between 2-6 units. (Anything above this is just too challenging). For example, let’s use a mechanized infantry company commander. We have decided to allow him to keep two of his organic mechanized platoons. Additionally, we have assigned him an armor platoon and attached an engineer platoon and a section of field artillery tubes. This makes for five subordinate units and a pretty significant amount of combat power. Remember, the more units you provide a commander the more flexibility and options you give him. However, this also increases the number of decisions the commander must make. This can place a heavy burden on some commanders and drastically slow down their decision cycle.

What do you need to know before you task organize your forces?

There is much that goes into creating your task organization. You must take many things into consideration when establishing units. These include the following:

- Clearly, the big three considerations are the unit’s mission, the commander’s intent, and the unit’s concept of operation. These are the principle drivers in establishing the task organization.

- You must understand doctrine. This includes knowing the capabilities and limitations of units and battlefield operating systems. You must know what missions are doctrinally feasible for units to conduct and just as importantly, what are not.

- It is critical you know the training and experience level of all your units. For example, has a unit trained or executed a mission you are considering them to perform – all the better. As we all can agree, experience matters.

- In any endeavor, morale is a significant factor. This should be taken into consideration when developing task organization. Especially critical is the recent combat experience of units. Clearly, combat is physically and mentally draining. Additionally, the psychological impact can be extremely positive, negative, or anywhere in between.

- The equipment a unit possesses must be taken into account. Within this area, look into things such as capabilities and limitations and the maintenance of the equipment.

- No one should know your unit better than the commander. This knowledge should include capabilities, limitations, strengths and weaknesses. These all enter the equation when forming a task organization.

- Within your plan, you should know the risks associated with it. These risks can be mitigated with the task organization.

- Obviously, you should know the current task organization that is currently in effect. This sets your base in which changes are made.

- Related to the above is knowing the ramifications changes to the current task organization will have. This could include things such as travel and supply concerns, breaking up combined arms teams, and degradation in overall cohesion.

- A complete understanding of a leader’s command and control capabilities is essential. You must know what types of units and the quantity of units a leader can successfully command and control.

“Organizing is what you do before you do something, so that when you do it, it is not all mixed up.”

A.A. Milne

Author of Winnie-the-Pooh

When do we task organize our forces?

Throughout the decision-making process for our mission, we will refine the task organization. During our course of action development, we will work with generic type units. For example, if you are a battalion task force, you will talk your course of action by saying a company composed of two armor platoons and one mechanized infantry platoon will …. Once you determine the course of action, you can start putting meat on the bone by translating those generic units into specific units. You will continue to refine this during the wargaming of the course of action. When the wargame is complete; you put pen to paper on the task organization when you craft your operations order. As you can see, we do not lock-in the task organization until late in the planning process. This allows for flexibility. This is not to say we are not going to have wholesale changes all the time on our course of action. This would be highly detrimental in terms of teamwork and cohesion. Thus, changes will be far more subtle.

How will a well-thought out task organization assist you in achieving mission accomplishment?

There are many ways a sound task organization can aid you in achieving your mission. Let’s touch on some of these below.

- Since you developed your task organization with two of your prime considerations being the commander’s intent and concept of operation, then it makes sense that your task organization should facilitate each of these. If it doesn’t, then you are clearly not setting the conditions for success.

- It should assist you in retaining flexibility during the execution of your mission.

- It should assist you in adapting to the overall environment. As we all know, the environment in which you are fighting is continually changing. Your task organization should help you in adapting to those inevitable changes.

- A good task organization should be prepared with an eye to the future. This means that you must plan for success. Doing this enables you to take advantage of those fleeting windows of opportunity. If you have to conduct wholesale changes to your task organization to execute these windows; you will miss the opportunity. These significant changes take time and too much expended time will close that window.

- One of the great things about task organizing is that it allows you to build combined arms teams. As we have discussed throughout the series, the utilization of combined arms gives a commander a clear advantage over his foe.

- Tied to the above is that a unit comprised of combined arms teams is likely to have mutual support amongst each other.

- An effective task organization will assist in promoting a unity of command within the organization as a whole. This unity of command is a tremendous asset in achieving success.

- It should maximize the strengths within the unit.

- It should aid in diminishing the weaknesses in the unit.

- It should be developed with a focus on exploiting enemy weaknesses and vulnerabilities.

- Related to the above is that it should hinder the enemy’s ability to utilize his strengths.

COMMAND AND SUPPORT RELATIONSHIPS

There are two important things that come out of the task organization when you move subordinate elements around – the command relationship and the support relationship. Subordinate units and the controlling unit must understand each of these explicitly. There can be no question in anyone’s military mind regarding each of these. Below we will discuss each.

What are the command relationships that exist in a task organization?

The command relationship within the task organization defines the command bond between the superior and subordinate units. (For clarification, a superior unit would be a company, while the platoons under it would be the subordinate units). It essentially lays out the chain of command for the mission. Within this relationship there are varying degrees of this bond. Some of this are very strong, while others are far more elastic. The more strong this bond, generally the longer this relationship is anticipated to exist. Obviously, the longer the relationship the more cohesion, understanding and teamwork you would anticipate exists between subordinate and superior units. Let’s define each of the command relationships that could exist.

Organic – Basically an organic relationship is one that has existed since the creation of the unit. For example, let’s look at a mechanized infantry company. Under the company would be three mechanized infantry platoons. These platoons would be organic. If the company would go into combat as is, we would call this fighting pure.

Assigned – In an assigned relationship, you will place a subordinate unit under a superior unit for a relatively permanent period. You will typically see this in a long campaign. In our above example, you may assign a tank platoon to the mechanized infantry company. This would be preferably be done even before combat operations so the company could train together. This is normally how you form combined arms teams.

Attached – In an attached relationship, you will place a subordinate unit under a superior unit for a temporary period. This is normally done for a specific mission. For instance, you may attach a tank platoon to a light infantry company to provide it extra firepower for a specific mission. This type of mission could be something such as seizing a key piece of terrain which is critical overall to mission accomplishment. Once the mission is complete, the relationship would likely end.

There are two other command relationships possible. These are Operational Control (OPCON) and Tactical Control (TACON). You will generally see these at the higher levels of command. To be honest, OPCON and TACON are a little difficult to explain. We will tackle these in ‘TACTICS 102’!

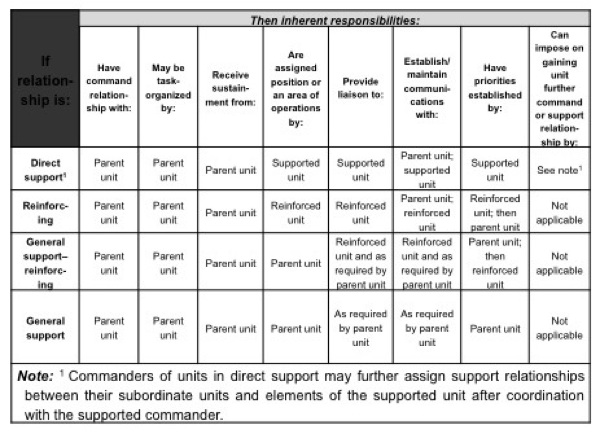

What are the support relationships that exist in a task organization?

Just as important as the command relationship is the support relationship. The support relationship identifies the purpose, scope, and effect desired by one capability when it supports another. Support relationships range from very exclusive to very broad. An exclusive relationship would be that the supporting unit is only supporting one specific unit. A broad relationship would mean that the supporting unit is supporting various units at one time. You will find support relationships in the world of combat support (field artillery, engineer, air defense, military intelligence, military police, and chemical) and combat service support (logistics). These units will likely be assigned a support relationship to a maneuver unit. These relationships will be identified in the task organization. We will explain the four different support relationships below.

Direct Support – In a direct support relationship, the supporting unit retains its command relationship with its parent unit. However, it is positioned by and has priorities of support established by the unit it is supporting. Example: A field artillery battery has been given a direct support role for an armor battalion. The battery stays under the command of its artillery battalion. Yet, it will be positioned and will shoot for the armor battalion. This is the most exclusive support relationship. Within the written task organization, the supporting unit would have a (DS) after it.

Reinforcing – In a reinforcing relationship, the supporting unit retains its command relationship with its parent unit. However, it is positioned by and has priorities of support established by the reinforced unit and then its parent unit. A reinforcing relationship can only be executed by the same type of units – artillery to artillery, engineer to engineer, etc… Example: A field artillery battery has been given a reinforcing role to another artillery battalion (not its parent unit). Its priority will be to shoot first for the battalion it is reinforcing and then to its parent battalion. Within the written task organization, the reinforcing unit would have a (R) after it.

General Support/Reinforcing – In a general support/reinforcing relationship, the supporting unit retains its command relationship with its parent unit. It is also positioned by and has priorities of support established by its parent unit and then by the reinforced unit. It will provide support to the force as a whole and will reinforce another similar type unit. Example: An intelligence radar battery has been given a general support reinforcing role to an armor brigade. The battery stays under the command of its military intelligence battalion. It will be positioned by its battalion and provide support to the entire force. Within the written task organization, the supporting unit would have a (GSR) after it.

General Support – In a general support relationship, the supporting unit retains its command relationship with its parent unit. It is also positioned by and has priorities of support established by its parent unit. It will provide support to the force as a whole and will reinforce another similar type unit. Example: An intelligence radar battery has been given a general support role. The battery stays under the command of its military intelligence battalion. It will be positioned by its battalion and provide support to the entire force. Within the written task organization, the supporting unit would have a (GS) after it.

Below is a chart which goes into more detail on the responsibilities:

What are some of the techniques in articulating a task organization?

All the analysis is complete and you have created a task organization that is sure to lead to mission accomplishment. However, if your genius is not articulated to the executors; your efforts are fruitless. You must be able to arrange your work into a format which is easy to comprehend. Fortunately, there are two proven methods available to you. These are the outline and matrix methods. The method that is selected is certainly whichever one you believe is best suited to the overall organization.

Based on our experience, generally the smaller the unit size the more conducive the matrix method is. This is because of several factors. First, normally it is the smaller size units which will utilize the matrix operations order method in capturing their entire order. Thus, it makes sense to use the same method in displaying the task organization for continuity sake. Second, the more complex the unit (which is usually the larger size units); the more challenging it is to use the matrix method. Consequently, the outline method is the more preferred and effective format for larger units.

Let’s provide you an example of each method and some explanation.

Outline Method

|

2/52 HBCT

1-77 IN (-)

1-30 AR (-)

1-20 CAV

A/4-52 CAV (DS)

2-606 FA (2×8)

TACP/52 ASOS (USAF) 521 BSB

2/2/311 QM CO 1/B/2-52 AV 2/577 MED CO (GRD AMB) (attached) 842 FST 2 BSTB

31 EN CO (MRBC) (DS) 63 EOD

2/244 EN CO (RTE CL) (DS) 1/2/1/55 SIG CO (COMCAM) 2D MP PLT

RTS TM 1/A/52 BSTB RTS TM 2/A/52 BSTB RTS TM 3/A/52 BSTB RTS TM 4/A/52 BSTB 2/54 HBCT

4-77 IN

2-30 AR

3-20 CAV 2/C/4-52 CAV (DS) 2-607 FA TACP/52 ASOS (USAF) 105 BSB 3/2/311 QM CO (MA) 2/B/2-52 AV 843 FST 3/577 MED CO (GRD AMB) 3 BSTB

A 388 CA BN 1/244 EN CO (RTE CL) (DS) 763 EOD 1030 TPD 2/2/1/55 SIG CO (COMCAM) 3D MP PLT

|

116 HBCT (+)

3-116 AR

1-163 IN

2-116 AR

1-148 FA

145 BSB

4/B/2-52 AV 4/2/311 QM CO 4/577 MED CO (GRD AMB) 844 FST 116 BSTB

366 EN CO (SAPPER) (DS) 1/401 EN CO (ESC) (DS) 2/244 EN CO (RTE CL) (DS) 52 EOD 1/301 MP CO 1020 TPD 1/3/1/55 SIG CO (COMCAM) 1/467 CM CO (MX) (S) C/388 CA BN 116 MP PLT

87 IBCT

1-80 IN

2-80 IN

3-13 CAV

A/3-52 AV (ASLT) (DS) B/1-52 AV (DS)

C/4-52 CAV (ARS) (-) (DS) 2-636 FA

A/3-52 FA (+) TACP/52 ASOS (USAF) Q37 52 FA BDE (GS) 99 BSB 845 FST 1/577 MED CO (GRD AMB) 3/B/2-52 AV 1/2/311 QM CO (MA) 87 BSTB

53 EOD 1010 TPD 3/2/1/55 SIG CO (COMCAM) B/420 CA BN 2 HCT/3/B/52 BSTB 745 EN CO (MAC) (DS) 1/1/52 CM CO (R/D) (R)

2/467 CM CO (MX) (S) 1/1102 MP CO (CS) (DS) |

52 CAB AASLT

HHC/52 CAB

1/B/1-77 IN (DIV QRF) (OPCON) 1-52 AV

4-52 CAV (ARS) (-)

3-52 AV (ASLT) (-)

2-52 AV

1 (TUAS)/B/52 BSTB (-) (GS) 2/694 EN CO (HORIZ) (DS) 52 FIRES BDE

HHB

TAB (-)

1-52 FA (MLRS)

3-52 FA (-) (M109A6) 1/694 EN CO (HORIZ) (DS) 17 MEB 52 ID

25 CM BN (-)

700 MP BN

7 EN BN 1660 TPD 2/2/1/55 SIG CO (COMCAM) 11 ASOS (USAF) 52 SUST BDE

52 BTB 520 CSSB 521 CSSB 10 CSH 168 MMB 52 HHB

A/1-30 AR (DIV RES) 35 SIG CO (-) (DS) 154 LTF

2/1/55 SIG CO (-)

14 PAD

388 CA BN (-) (DS)

307 TPC

|

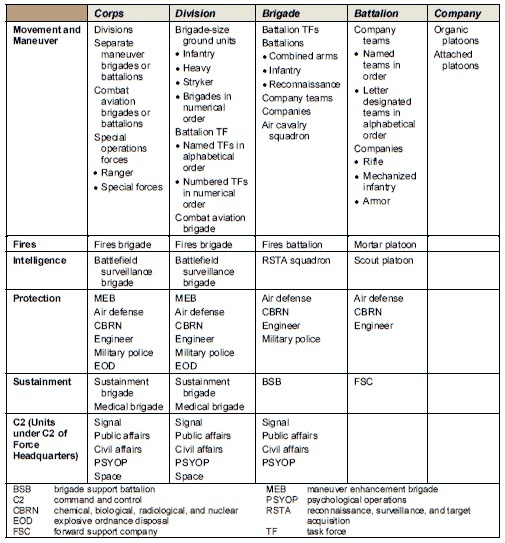

So how did we come up with the above in terms of order? Will it wasn’t a random act. There is a list of doctrinal rules and they are followed. In the chart below, you will find the order in which we list units in the task organization.

Order for listing units in a task organization

Additionally, per US Army doctrine, here are the rules which were followed in the task organization:

Group units by C2 headquarters. List major subordinate maneuver units first (for example, 2d HBCT; 1-77th IN; A/4-52d CAV). Place them in alphabetical or numerical order. List brigade combat teams ahead of brigades, combined arms battalions before battalions, and company teams before companies. Follow maneuver headquarters with the field artillery (for example, fires brigade after maneuver brigades), intelligence units, maneuver enhancement units, and the sustainment units.

Use a plus (+) symbol when attaching one or more subelements of a similar function to a headquarters. Use a minus symbol (–) when deleting one or more subelements of a similar function to a headquarters. Always show the symbols in parenthesis. Do not use a plus symbol when the receiving headquarters is a combined arms task force or company team. Do not use plus and minus symbols together (as when a headquarters detaches one element and receives attachment of another); use the symbol that portrays the element’s combat power with respect to other similar elements. Do not use either symbol when two units swap subelements and their combat power is unchanged. Here are some examples:

1 C Company loses one platoon to A Company; the battalion task organization will show A Co. (+) and C Co. (–).

1 4-77th Infantry receives a tank company from 1-30 Armor; the brigade task organization will show TF 4-77 IN (+) and 1-30 AR (–).

When the effective attachment time of a nonorganic unit to another unit differs from the effective time of the plan or order, add the effective attachment time in parentheses after the attached unit—for example, 1-80 IN (OPCON 2 HBCT Ph II). List this information either in the task organization in the base order or in Annex A (Task Organization). For clarity, list subsequent command or support relationships under the task organization in parentheses following the affected unit—for example, "…on order, OPCON to 2 HBCT" is written (O/O OPCON 2 HBCT).

Give the numerical designations of units in Arabic numerals, even if shown as Roman numbers in graphics—for example, show X Corps as 10th Corps.

During multinational operations, insert the country code between the numeric designation and the unit name—for example, show 3rd German Corps as 3d (GE) Corps. (FM 1-02 contains authorized country codes.)

Use abbreviated designations for organic units. Use the full designation for nonorganic units—for example, 1-52 FA (MLRS) (GS) rather than 1-52 FA. Specify a unit’s command or support relationship only if it differs from that of its higher headquarters.

Designate task forces with the last name of the task force commander (for example, TF WILLIAMS), a code name (for example, TF WARRIOR), or a number (for example, TF 47 or TF 1-77 IN).

For unit designation at theater army level, list major subordinate maneuver units first, placing them in alphabetical or numerical order, followed by fires, intelligence, maneuver enhancement, sustainment, and any units under the C2 of the force headquarters. For each function following maneuver, list headquarters in the order of commands, groups, brigades, squadrons, and detachments.

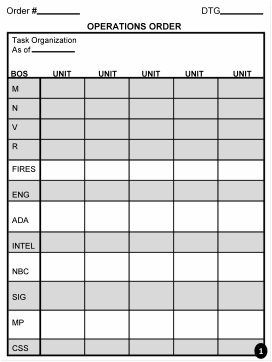

Matrix Method

You dedicated readers out there remember our article on the matrix order several months. http://armchairgeneral.com/tactics-101-066-the-matrix-operations-order.htm

Above you will find a template for articulating your task organization. As highlighted earlier, the matrix format is best served for smaller units. In the matrix format, you place your major subordinate units on the top row. If this is a battalion task organization, then you will utilize your subordinate companies. Underneath each of the companies, you will identify the subordinate units under them. As in the outline method, we will also identify any of the particulars such as the command and support relationships. Once again, since this method is generally utilized for smaller units; you should not see much complexity here.

REVIEW

The development of a task organization is an important action in any plan. You must determine how you can best utilize your forces and assets to give you the best opportunity to achieve success. In developing this task organization, you must come to the plate with the complete understanding of your entire unit. This includes areas such as strengths, weaknesses, capabilities, and limitations. Devising a sound organization is not enough. You must take the next step and articulate it to your subordinates. This articulation includes knowing the command and support relationships that exist. As our article has shown, there is much that goes into developing a task organization. If it is considered an afterthought, the unit as a whole will pay a heavy price.

NEXT MONTH

We will change it around a bit in our next article. Our focus in the upcoming month will be on noncombatant evacuation operations. You may know it simply as NEO. In NEO, the purpose is to evacuate civilians, who are located in foreign countries, caught in the middle of war, civil unrest, and natural disasters. We will discuss the principles of these operations and reflect on some case studies. Some of these turned out well and others not so successful.

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks